When Coral’s teacher told me at pick up, “There’s a birthday party invitation in Coral’s backpack,” I did a double take. Coral has been invited to very few kids’ birthday parties. She has attended many parties, usually family birthdays or birthday parties Tate has been invited to, but it’s extremely rare for her to receive her own invitation. Part of the reason for this is because her friends in her special education class often have smaller (and less overwhelming) parties, just as we do for Coral.

Once I arrived home I opened the invitation for Kate’s 7th birthday — a girl in Coral’s general education first grade class. Knowing that attending a crowded birthday party could be challenging for Coral, I needed to make sure the location would be accessible to her. The party was going to be at the park right by Coral’s school (a location she is familiar with) and on a day and time that worked for us. I told Coral about the party and put it on the calendar. We would try to attend.

The party day arrived, along with some anxiety. Unlike other birthday parties, I didn’t really know these parents or kids. My mind played ping pong with different thoughts and questions: What if Coral has a meltdown? Will she enjoy the party? Will the kids be happy she is there? I did my best to come back to the present moment, knowing that predictions about the party were futile. I didn’t have to live the party twice — once before and once during the actual party.

We arrived to the park a bit late because Coral fell asleep in the car on the way over. I had a bag packed with her favorite snacks and toys, and I draped her AAC device (her “talker”) over my shoulder. I carried a large blanket under one arm and held Coral’s hand in my other. I said some silent prayers that she would walk the entire way over to the party. With all of the extra stuff, it would be challenging to try to get her up, if she decided to drop to the ground mid-walk.

At the party I put our stuff down and began to walk with Coral towards some of the kids. A little girl named Sarah came skipping over with a huge smile. “Hi, Coral!” she beamed. She held out her hand, “High five?” Coral looked at Sarah’s hand. Realizing Coral was not going to reciprocate her high five, Sarah smiled and dropped her hand down. “I’ll see you, Coral,” she said as she skipped off. I was taken aback with pleasant surprise at the comfort and friendliness Sarah showed when greeting Coral. Other kids are often reserved and slightly awkward in their interactions with Coral, confused by how she plays differently and doesn’t use spoken words to communicate.

We walked over to the playground, but Coral only wanted to lay on the concrete. She seemed slightly agitated and did not want to play on the equipment like she often does. From there, we started down a slippery birthday slope, as I attempted to help Coral (and myself) regulate in the different and capacity stretching environment.

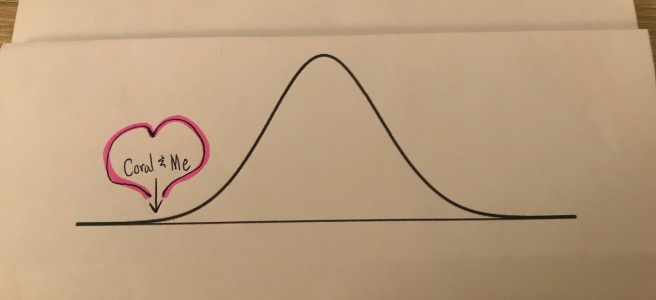

I watched as about 15 kids lined up to take their turn at the piñata, while parents snapped photos. Coral was lying across my lap and did not want to get off of the blanket to join the kids. She alternated between throwing toys off of the blanket with frustration and eating some snacks. As I sat there watching the kids and parents, I simultaneously watched my mind fill with emotions and thoughts. For all the mental work I’ve done over the past 7 years, emotions related to Coral and Dup15q syndrome still come up at unexpected times. I took some deep breaths, glad I was wearing sunglasses.

I eventually got her to stand up and walk over to the food table. I saw that the pizza was all gone. The birthday girl’s dad, who I met right there, was standing by the table. We started to talk in what turned into an awkward conversation — one when a parent of a nondisabled child (due to lack of perspective and experience) talks about topics that are unrelatable to a disability parent. His intentions were good, but (like most parents at the party) he had no idea about Coral’s needs, abilities and disabilities. He was talking about his daughter. At one point he casually asked, “Isn’t it so cool to hear about their new friends and their day at school?” I could only smile and nod, lost for words.

I could tell Coral and I were getting close to needing to leave to preserve any remaining emotional and physical capacity, but I wanted to stay for the birthday song. As I deliberated, Coral had a diapering emergency. With no large changing tables available in the park bathroom, I had to jerry rig changing her in the back of our van, while trying to maintain her privacy. By the time we returned, they had already sung happy birthday (one of Coral’s favorite parts of a birthday), and there wasn’t any cake left (something else she enjoys).

I decided it would be best to say our “goodbyes,” gather our things and head home. I walked with Coral over to Kate’s mom to thank her for inviting us and for hosting the party. When I was talking to her, Coral looked up at her, walked towards her and leaned in for one of Coral’s sweet cuddly hugs. I smiled and looked at Kate’s mom’s face. It immediately softened, as she smiled — a look of comfort and ease replacing any previous discomfort.

As we drove home, I reflected on the party and why we came in the first place. I realized that in coming I didn’t need Coral to stand in line to swing at the piñata. I didn’t need her to sing the happy birthday song with words. I didn’t bring Coral to the birthday party to check typical accomplishments off of a list — to somehow prove that Coral could (in some way) be neurotypical.

I came because Coral was invited. She has never been invited to a general education classmate’s party. I came to meet them halfway. If you invite Coral, she will come.

I came to let Coral be a part of the party in whatever way was comfortable for her, even if I had to spend a substantial amount of time in my own discomfort.

I came so the parents of her classmates could meet her and finally put a face to a name — to bring the human side to whatever perception they may have had about her disabilities. I came so they could see that Coral is really just a 7 year old child who has her own preferences and ways of doing things, like their own child.

People often say, “There’s no guidebook on this disability parenting path.” To an extent that’s true, but I think Coral and I are writing our own book. We’re learning what works: how to respond to certain situations, how to navigate the varied emotions that arise (even at surprising times), and how to approach situations with flexibility and even curiosity.

On this path, I am learning that where there is despair, there is an opportunity to find hope. At a party full of reminders of how challenging it can be to find accessible events for Coral and how isolating this parenting experience can feel at times, there are glimmers of hope.

If we hadn’t attended the party, we both probably would have been more comfortable. But attending the party offered some important reminders of hope. Where some may be uncomfortable around disability, there are the Corals who help them connect with a shared humanity and capacity for love. Where some would never invite Coral to their birthday party, there are the Kates who include her. Where some struggle to connect with Coral, there are the beaming Sarahs who choose to see Coral not only as a peer but also as a friend.

Three very different girls. Three important glimmers of hope.

These are not isolated incidences but reminders of what can be — in any moment and in any place — if we’re courageous enough to see beyond the challenge and despair that may be present, too.